Get this writing exercise in a printable, mini-comic format: [PDF].

Constrained writing…

The other day I hacked a little skit based on Austin’s mini-comic about writing with the Fibonacci sequence. So then I got to thinking about other arbitrary limits. What else could I do, just to get the brain wiggling? Still in math mode, my firs…

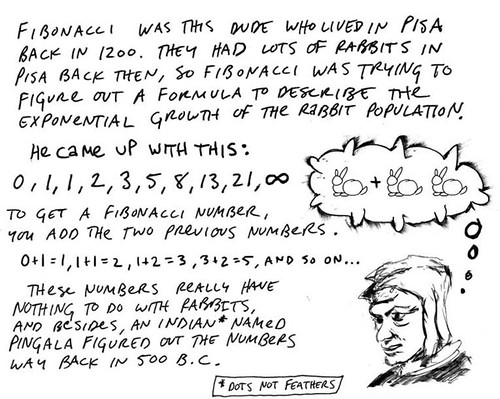

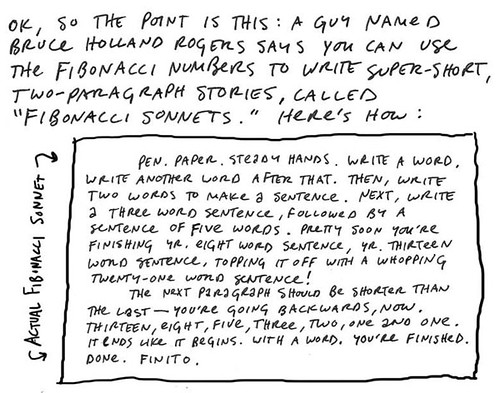

[…] Writing The Fibonacci Sonnet […]

This site participates in the Amazon Affiliates program, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.

Cool. And I suppose one could do the same thing with other creative elements. In comics, for example, you could play with panels per page, characters per panel, # of simultaneous conversations, # of expanded fold-outs per page, etc. And it seems like each of those also imply their own story. Very cool. Thanks!

And I suppose no one but me ever met the person who claimed to have solved this mathematical riddle…

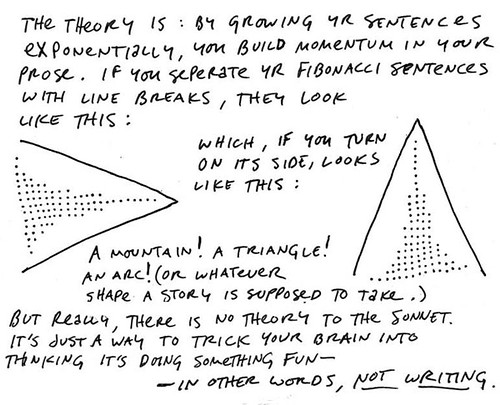

I was with you up until the “not writing” part — why is this not writing? There’s a theory here, but one that’s mathematical and potentially much deeper than the folk psychological theories we have which usually inform how people craft writing. Human beings perceive increases and decreases in Fibonacci sequences to be just what you said, a “piling on” of words, and that’s a useful technique in writing.

Sean, I think it’s talking about taking the pressure off of writing, i.e. you get focused on the game / formula piece of the puzzle and you just let yourself *write* instead of psyching out about it.

This is similar, I think, to the sort of work that Georges Perec & crew used to do, working with anagrams, schematized stories, etc.

Mark: you’re right — it’s perfect for comics layouts, too. Check any Chris Ware page.

Professor Sean: Tim’s right. What I meant was, “You’re tricking your brain into thinking it’s not Writing.” As in, “Writing is Hard Work.” This is very much Writing, which is why I call it a writing exercise. Just a way to get to that play state.

Those of us who are poets working with not only meter but (sometimes) rhyme schemes and any number of strict formats have to develop the discipline to combine free-association (go where the story leads you) with intense structure. There is an achievable balance, when you’re lucky or gifted, that creates something the human brain devours like savory truth. Think Frost’s “Stopping in the Woods on a Snowy Evening” — a perfect marriage of simple visuals with complicated structure (alliteration, assonance, and four quatrains of four feet each in perfect iambic tetrameter). I can imagine using the rigor of a Fibonacci sequence to create Great Writing in the same way that haiku, tanka, etc. give the poet a challenge that can only be adequately met with language chaos once inside the conceit of format. I personally broke free into my zone as a writer once I stopped giving myself “free rein” and instead became, as Annie Lamott says, a writer who “writes because it will kill me if I do not”. This was sparked by a program I heard on NPR a long while ago where some composer talked about being inspired by Pablo Neruda’s decision to write a poem a day for a year. The composer decided to write a piece of music a day for a year, and talked about how it rearranged his brain. I began writing a poem a day — no excuses — and instead of shoving out drek just to meet the obligation, my writing exploded and I began winning awards.

My bad, I misinterpreted.

But I ain’t no professor no more!

Austin, I love the cartoon and the Fibonacci sonnet that tells how to write a Fibonacci sonnet.

I just returned from Finland where I was teaching a seminar on how to teach creative writing, and we spent a lot of time on the various ways to get new ideas and push those ideas to be newer still. There are many existing fixed forms that writers can use, but teachers and writers can create brand new forms, too. A big component in teaching creative writing is reminding writers that they *can* have fun writing and that the lack of ideas is no excuse for not writing.

Anyway, nice to stumble onto this.