FIRST PASS

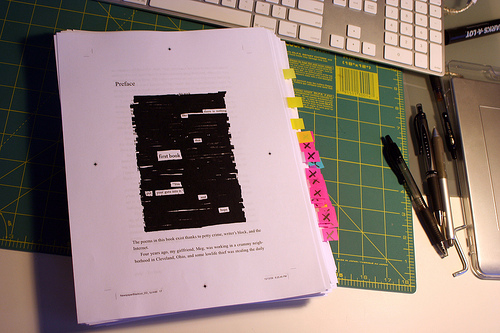

Meg and I spent a good bit of the weekend going over the first pass of Newspaper Blackout. “First pass” is the author’s first chance to see the book all typeset and designed and actually looking like it will when it’s printed as a book. It looks really, really great. There are a few changes still, but it’s so incredibly close to being ready.

And still, 24 weeks to pub date…

DON’T WORRY ABOUT UNITY

Don’t worry about unity from piece to piece. What unifies all of your work is the fact that you made it.

I tweeted this a few days ago, and my Twitter friend John T. Unger (@johntunger) replied,

Keep making things. Don’t worry about how it all fits together right now.

THE SAME SWORDS

NEWSPAPER BLACKOUT PRINT GIVEAWAY!

Four years ago today I made my first newspaper blackout poem, and to celebrate the anniversary, I’m giving away a signed, limited-edition print of “Overheard On The Titanic,” hand silkscreened by my friend, painter and printmaker Curtis Miller:

YouTube: Silkscreening Newspaper Blackout Prints

There were only 18 of these babies made: one is hanging on the wall in my library, sixteen are in a flat file waiting to be sold in the distant future, and one could belong to you.

All you have to do is leave a nice comment below, or tweet with the hashtag #newspaperblackout some time in the next week before next Monday, Oct. 26th, Midnight CT. I’ll pick the winner at random.

The giveaway is now closed. Congrats to the winner, Matt Wilson, and thanks to everyone who entered! More contests to come.

After that, you can browse the new Newspaper Blackout Archives or read my favorite poems from 2006-2008.

Thanks so much to everyone for reading! Y’all rock.

- ← Newer posts

- 1

- …

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- …

- 644

- Older posts→