During my daily reading of Thoreau’s journal, I came across an entry from October 28, 1853, 164 years ago, in which he writes about getting back 706 of the 1,000 printed copies of his first (self-published) book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. (“Of the remaining 290 and odd, 75 were given away, the rest sold.”) His “publisher, falsely so called” said that “he had use for the room they occupied in his cellar.” Thoreau had the remainders sent to his house by wagon, and he carried them all upstairs “to a place similar to that to which they trace their origin.”

They are something more substantial than fame, as my back knows, which has borne them up two flights of stairs to a place similar to that to which they trace their origin… I have now a library of nearly 900 volumes, over 700 of which I wrote myself. It is not well that the author should behold the fruits of his labor? My works are piled up on one side of my chamber half as high as my head, my opera omnia. This was authorship, these are the works of my brain.

He tried his best to see it all in a good light:

I can see now what I write for, the result of my labors. Nevertheless in spite of this result, sitting beside the intert mass of my works, I take up my pen to-night to record what thought or experience I may have had, with as much satisfaction as ever. Indeed I believe that the result is more inspiring and better for me than if a thousand had bought my wares. It affects my privacy less and leaves me freer.

“There’s nothing quite like an author’s excitement upon beholding his first book,” writes Laura Dassow Walls, in her biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life. And there’s nothing quite like watching a book fail to sell, particularly your first one. (My first book sold decently for a poetry book, and finally earned back its advance a couple years ago, but I think most readers sort of forget it exists. Honestly, I don’t mind. Sometimes you need your first book to not be a total failure, but to be a little bit embarrassing, so you’ll go on to write another one…)

Reading about Thoreau’s piles of remaindered books, I couldn’t help but think of Clive James’ deliciously nasty poem, “The Book of my Enemy Has Been Remaindered,” that begins:

The book of my enemy has been remaindered

And I am pleased.

In vast quantities it has been remaindered

Like a van-load of counterfeit that has been seized…

The narrator of the poem goes on to admit, “Soon now a book of mine could be remaindered also,” but in his case it will be “due / to a miscalculated print run, a marketing error — / Nothing to do with merit.”

Of merit vs. business model, Laura Dassow Walls points out that Thoreau’s first book was pretty much doomed from the beginning. His literary agent was begging him to send shorter pieces to publish and build up his fame before he put out a book. He was giving well-received lectures on his days at Walden, and if he wanted to release a book, he probably should’ve been focused on that one. But instead, he agreed to terrible terms with his printer, James Munroe, who was recommended to Thoreau by his pal Ralph Waldo Emerson. Of the 1,000 books printed, Munroe took the printing costs out of the sales, and if the book didn’t sell, “Thoreau would guarantee reimbursement in full.” His family worried, thinking it wouldn’t sell, but Emerson urged him to go for it. Big mistake.

[Munroe] didn’t publish books; he only printed them. He refused to advertise, and he had no distribution network. One could purchase Thoreau’s book only at Munroe’s shop in Boston or by ordering it from Munroe by mail. This business model had worked for Emerson, who was already well known and whose fame was centered in Boston. But for a first book by an unknown author seeking a national audience, it was a disaster.

Walls writes that “while the book is a flawed masterpiece, it is still a masterpiece,” and “had it been truly published, rather than printed and laid into storage” it would’ve announced Thoreau’s potential, even though “[it] would never have found a wide audience.”

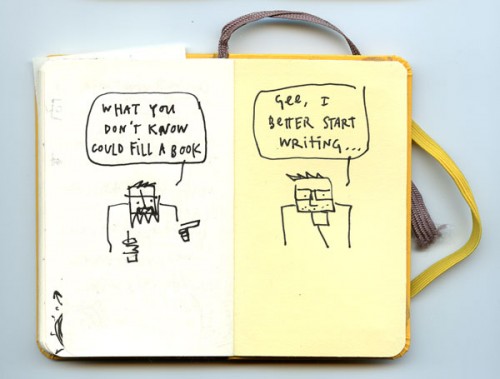

But that’s the thing about the first book, the second book, or even, should you be lucky enough, the 17th book: There’s always the question of the next book — where it will come from, what it will be, and what will become of it…