Very glad to see that Tara Wray put up a teaser trailer for “Cartoon College,” her forthcoming documentary about the Center for Cartoon Studies, at the Cartoon College Myspace page.

SAUL STEINBERG’S REFLECTIONS AND SHADOWS

This book is the fruit of tape-recorded conversations held in my country house in Springs, East Hampton, during the summer of 1974 and the autumn of 1977, with my friend Aldo Buzzi, who later made a careful selection of all the transcriptions and arranged them in four chapters.”

—Saul Steinberg

Reflections and Shadows is a short book, but full of little gems. Here are a few of them:

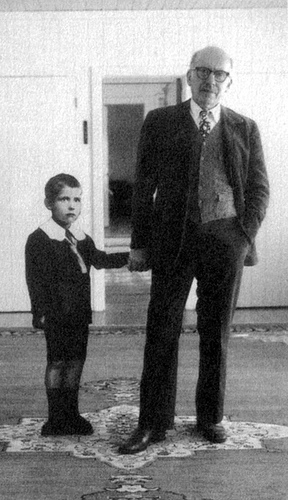

Saul Steinberg holding his eight-year-old self by the hand.

* * *

On Memory:

“Nothing that has been deposited in the memory is lost. Memory is a computer that all one’s life goes on accumulating data which are not always used, since man is often like an ocean liner that sets sail with only a single cabin occupied. We ought to be able to use this huge accumulation of data continually, keep it functioning, combine and multiply its elements and reintroduce them into the circuit of our thoughts….Maybe I’ll have the good fortune to find again other things that now seem forgotten. I’d like to be able to go back and see all the things that at the time I stored away without perceiving them, follow myself at the age of ten and judge, with the mind of today, the conditions under which I lived, thus discovering what, at that time, had been deposited in the computer without my knowing it.”

On Drawing Family Members:

“Nowadays I draw uncles and aunts from photographs and I recognize (looking at them for the first time as real people) parts of myself, an ear, an eye. Archaeology!”

A Definition of Family:

“…people I had neither invented nor found for myself.”

On Leaving the Past to Memory:

“[There] are places that don’t belong to geography but to time. And the memory of these places of sadness, of suffering, but above all of great emotions, is spoiled by seeing them again. It’s better to leave certain things in peace, just the way they are in memory: with the passage of time they become the mythology of our lives. I haven’t even wanted to see certain people again with whom I had been more or less friendly in terms of time and place: schoolmates, childhood companions. You can’t resume a dialogue that never was a real dialogue but rather a temporary complicity, the kind of complicity established among people occupying the same compartment in a train.”

On Americans and Food:

“In America you don’t ask passersby to point out a good restaurant, as you do in Italy or France. People don’t understand what a good restaurant is, because here one goes to a restaurant not to eat but to have a good time. To answer, they’d have to know why you want to go: to pick up a girl, to take the family and have an unforgettable evening with music and soft lights, to gorge yourself or have a quick snack. They wouldn’t even be able to say whether some diner is good or bad: a diner is a diner.”

On the Jukebox:

“…built according to the laws of the Catholic or Chinese or Hindu altar, a magical object to be worshipped because all good things come from it: music, dance, love, and joy.”

On drawing from life:

“It’s hard to do a portrait. You must first spend a critical moment in which you quickly — if you’re lucky — discard all the commonplaces about the subject of the drawing. More difficult than inventing is giving up accumulated virtues. The things you discovered yesterday are no longer valid. It’s impossible to find anything new without first giving something up.

There’s a moral in this. It’s stinginess that holds us back, especially when we’re not only enamored of what we’ve discovered but also convinced it’s good. There are those who, in working from life, continually use the baggage they picked up yesterday; they work from life without really looking, without working from life.”

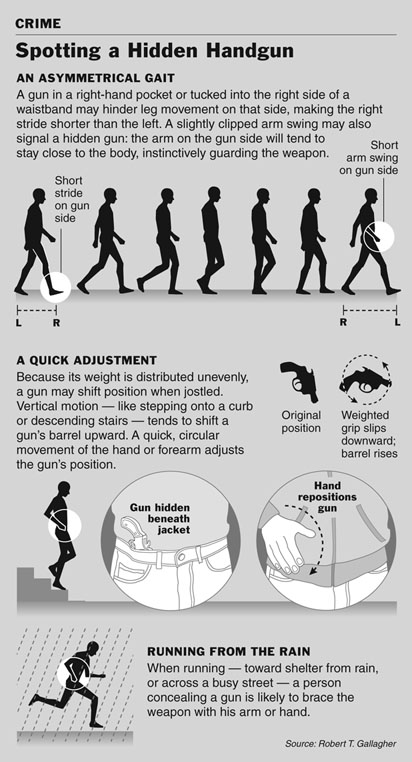

MEGAN JAEGERMAN’S INFOGRAPHICS

Edward Tufte points out the great infographics work of Megan Jaegerman, some of whose work is featured in Beautiful Evidence.

Megan Jaegerman produced some of the best news graphics ever done while working at The New York Times from 1990 to 1998….To create this display, [she] did both the research and the design, breaking their common alienation. This design amplifies the content, because the designer created the content.

When I visited an information design studio during a school visit to Carnegie Mellon, the professor asked me for my input on some of the student projects, many of which were infographics like this. I kept blathering on about how much they could be considered comics. I said one girl’s work was basically a hieroglyphic, and one guy’s work was like a Family Circus neighborhood map (I’m not sure he took that as a compliment).

I Googled Megan Jaegerman and couldn’t find anything else out about her. Anyone have any leads?

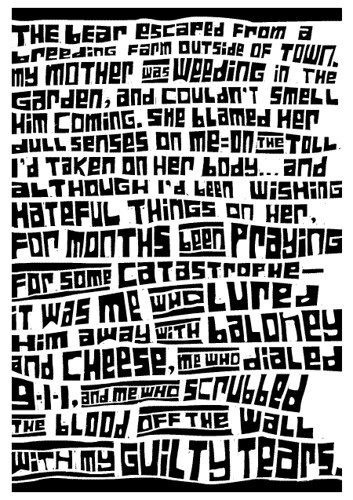

HAND-LETTERING

David Heatley has a cool post about hand-lettering, and points out his mentor, Robert Wakeman. For me, hand-lettering is an essential part of comics: the words need to look like they were drawn by the same hand as the art, or the whole “unity of style” is shot.

Even when I’m doing my woodcut-style comics I letter by hand. Here’s a comics page erased to show only the lettering:

Here’s one of my cut-out fictions, done spontaneously by carving out the words as I went along:

Ray Fenwick does comics which are almost exclusively defined by his hand-lettering. Great stuff.

THE WEATHER AS A COMIC STRIP

Sometimes the five-day forecast strikes me as the simplest, best comic strip ever:

They’re little stories, aren’t they?

- ← Newer posts

- 1

- …

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- …

- 86

- Older posts→