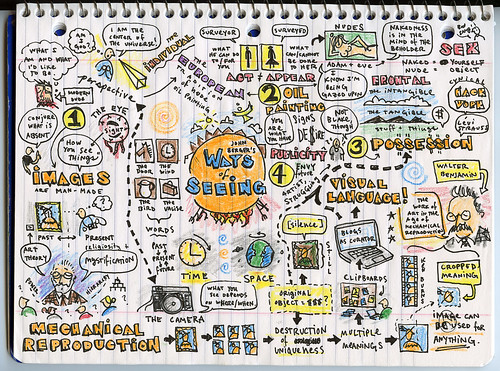

Fantastic book based on the 1972 BBC miniseries, which someone has uploaded to Youtube, and I’ve assembled into one handy playlist for your viewing pleasure. Amazing how much the contents remain valid in the age of the internet.

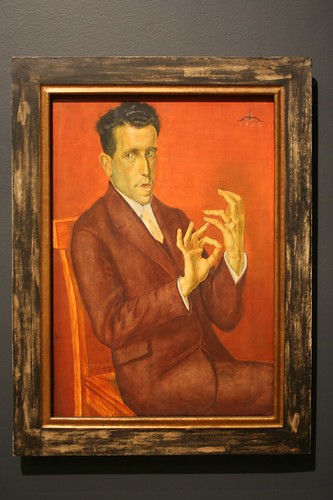

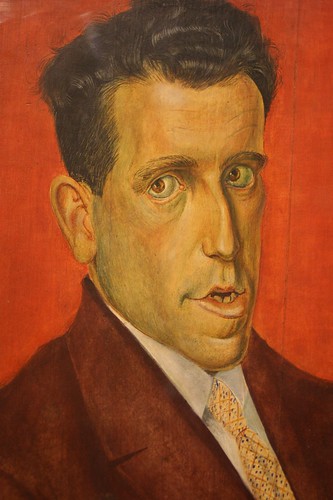

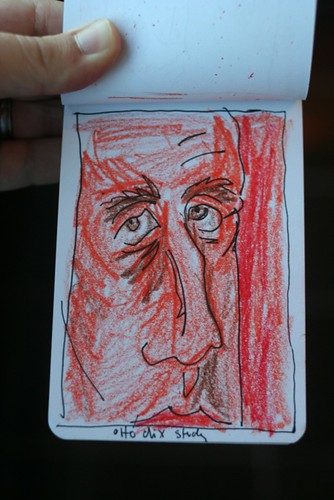

The first essay is about art in the age of photography and reproduction, and is based on Walter Benjamin‘s essay, “The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin’s idea was that in an era where an image can be easily reproduced, art might be “freed up” and become available to a mass audience.

I’ve recently been going back and forth with an artist friend of mine about his fine-arts-based world (where his collectors value the original, one-of-a-kind) and mine (where there is no original, only reproductions, on the blog, in the book, etc). Our ideas about making art are very similar, but our business models couldn’t be more different!

I was with him and our wives at an opening in an art gallery in town last night and couldn’t get over how uncomfortable I felt about the whole thing. There was free beer, sure, but no artist’s statement, no postcards, nothing. There was only a photocopy of the price list, along with some goofy map of the exhibit that related “culture vs. nature” or something cliched along those lines…

Why so uncomfortable?

First, the idea that anyone has $10,000 to spend on a piece of art boggles my mind. Second, I find it alienating, as someone without the $10,000 to spend on art, to not be able to “own” or “buy into” or “take home” some part of the work. Regardless of how much you love the art, there’s nothing he can sell to you, there’s nothing you can buy into, no way for you to show your support or love for the work. All you can do is snap a bootleg shot on your camera phone. You feel like a f*&%ing second-class citizen: You can look, but don’t touch. It’s worse than a museum: at least in a museum you can buy a postcard or a book in the gift shop.

Contrast this with my experience at Maker Faire earlier in the day, where the idea was: come make things with us. Everyone is encouraged to join in.

Take our friends Bleep Labs. They had:

- Robots on sale for $125

- T-shirts on sale for $20

- Stickers for free

Art in the age of mechanical reproduction, indeed! Every level of merchandising was covered.

More thoughts on this to come.