In my life, the two women I’ve spent the most time around are my mom and my wife.

They both love to cook. They both own sewing machines.

They both love Martha Stewart.

They love Martha Stewart because they’ve learned from her. They trust her. They buy her books and her products because they feel loyal to her.

They love Martha Stewart kind of like I love Lynda Barry.

* * *

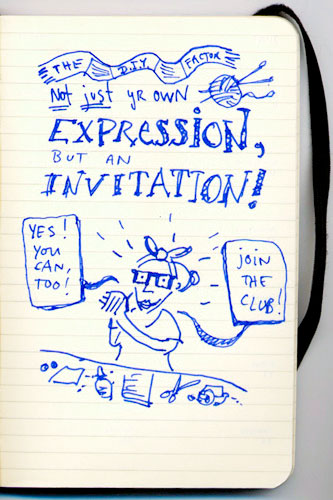

A year ago I was sitting in a craft store here in Austin. I sat and doodled and ate cupcakes and watched my wife and all these women crafting, teaching each other, helping each other. There was such a sense of inclusiveness. It was as if everyone was saying to each other, “Yes! You can do this! We can do this! Join the club!”

Not long after that, I was watching a profile of Rachel Ray on TV. The folks who knew Rachel seemed to suggest that her success was not necessarily attributed to her abilities as a cook, but rather to her attitude and energy she projected to her viewers. The number one thing she was giving them was encouragement. She wasn’t just teaching them, she was saying, “You can do this!”

I started surfing some of the craft blogs my wife loves to read. It was a total revelation: by sharing and teaching, these women gained readers and loyal fans, and then sold their wares on Etsy and in books to those loyal fans.

And I realized: if artists want to learn a good business model, they should look to the craft community.

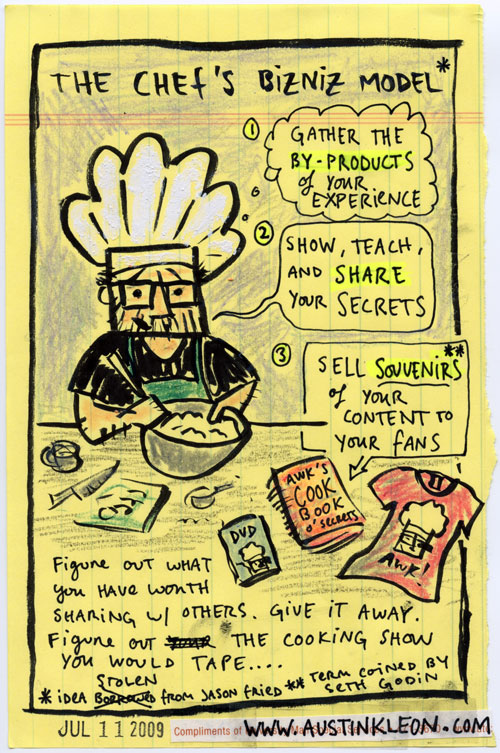

Turns out I wasn’t the only one thinking this way. Jason Fried, the founder of the software company 37 Signals (they have a terrific blog), when he gives a talk, he often claims that chefs are the best business entrepreneurs, because they know that sharing leads to more sales. He suggests that businesses emulate famous chefs. My friend Tim Walker summarized this bit in his notes on Fried’s 2008 SXSW session:

Fried notes that the famous big-name chefs (Emeril Lagasse, Mario Batali, et al.) SHARE a lot. Here are these big experts who are authorities in their field, and yet they’re sharing everything they know. Along the way they collect money from willing customers/users who buy their cookbooks, eat at their restaurants, buy their sauces at the grocery store, etc. Fried says you should figure out what it is YOU do that you can share with everybody else.

(I saw the same idea pop up in my friend Mike Rohde‘s sketchnotes of a Fried talk.)

What Fried said in a recent talk was: Figure out your what’s cooking show. Figure out what’s your cookbook.

Figure out how to be your own Martha Stewart!