Last January, after seeing a couple of my newspaper blackout poems, Winston Smith e-mailed and recommended to me a book called “A Humument” by an artist named Tom Phillips. In the mid-sixties, Phillips took an old Victorian novel by W.H. Mallock called “A Human Document” and started blacking out the pages to make a new book, ” A Humument.” Well, I thought this sounded pretty interesting, but was too lazy to look it up, or even Google it, and pretty soon I’d forgotten all about it.

A year later, Drew Dernavich e-mails me a link to Humument.com, the official site of the book! Little did I know that you can see every page from the book online. (There’s also a new edition you can buy online from Amazon.)

Too cool.

There’s been a few images from this in Art in America, too.

Tom Phillips at Flowers

Art in America, Oct, 2005 by Faye Hirsch

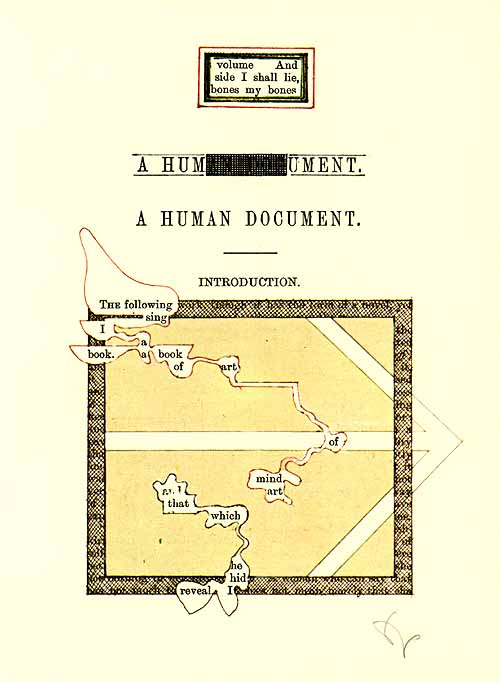

In the late 1960s, needing a source that would serve for the cut-up technique he was then exploring, the British artist, writer and composer Tom Phillips came across an obscure late-Victorian novel, A Human Document (1892), by W. H. Mallock. He began “treating” the book, radically abridging the overripe text with poems “found” within each page and distributed over it in blurbs something like speech bubbles. These he connected by “rivers” charted through the original type. Over the remainder of the page and obscuring it, Phillips painted and drew images, sometimes related to the poems and sometimes not.

By 1973, Phillips had entirely treated the 367 pages of A Human Document, retitled A Humument; in 1980, it appeared in a trade version (issued then and now by Thames & Hudson). Periodically, Phillips makes new treated pages (from other copies of Mallock) to replace the old, with the intent of eventually creating A Humument all over again. The fourth edition, issued this year, was the occasion for the Flowers show, which presented unique Humument spin-offs, including 20 collages from 2005 (the “Humument Fragment” series), an earlier 26-part alphabetic meditation on art (Aspects of Art: A Humument Alphabet, 1997) and the 1973 10-part Out of Africa, all utilizing texts from A Human Document but separate from the ongoing book project.

You can compare the new edition of A Humument with the first, fully reproduced at humument.com; if you happen to have any of the others at hand, you can compare them, as well, observing the snake shed its skin, as it were. A Humument was clever, mysterious and funny from the outset and it remains so, with its recurrent characters (“Toge” and “Irma,” linked in erotic escapades both visual and textual), bits of nature, philosophical fragments and endlessly amusing observations on art (three letters that, thankfully, are abundantly conjoined in the English language). The imagery varies considerably–landscapes with watery wraiths, the artist’s signature stenciled letters and numbers, invented scripts, mini-galleries dedicated to abstraction, scratchy allover grids, etc. Poems tend toward the terse and, of course, concrete, at once playfully nonsensical and miraculously, novelistically, coherent.