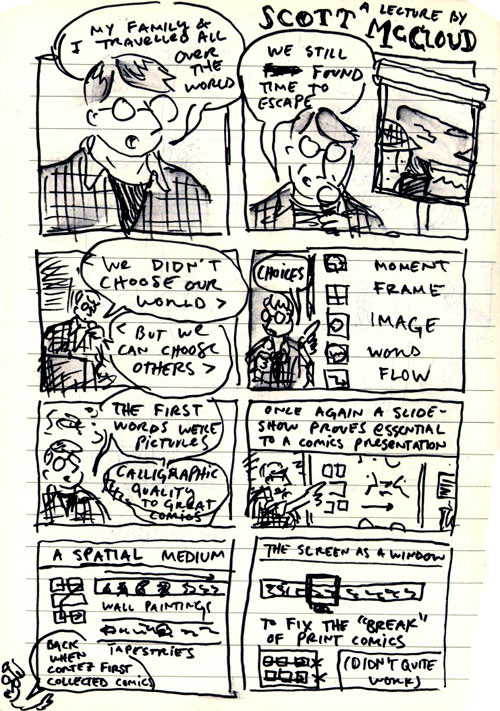

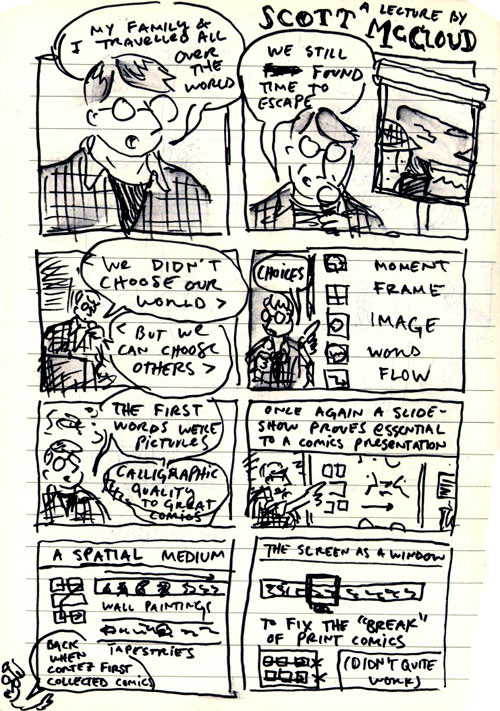

Meg and I stayed late after work/school and went to see Scott McCloud tonight at UT:

UPDATE: Here’s the Daily Texan on the talk.

Meg and I stayed late after work/school and went to see Scott McCloud tonight at UT:

UPDATE: Here’s the Daily Texan on the talk.

David Hockney argues that the use of optical lenses probably had something to do with the widespread the 15th century method of perspective:

…the [optical] projection yields up one-point perspective–and nothing else does. It’s difficult nowadays, in a world saturated with television and photographs and billboards and movies, to recall how radically new one-point perspective would have appeared to those first exposed to it. That’s not how the world presents itself and can’t help but present itself through a one-point projection, be it a pinhole or a lens or a curved mirror.”

We see with two eyes. It’s called “binocular vision.” Each eye receives a slightly different image, and the brain processes the two images into 3-D to generate the sensation of depth.

Western one-point perspective is an attempt to fabricate this sensation. It is an illusion. Hockney calls it “the point of view of a paralyzed cyclops.”

And when it comes to comics, some of my favorite artists choose to completely ignore it.

Here’s Scott McCloud from Making Comics:

Dig this funky Grosz. See a vanishing point?

What about this Ron Rege?

Death to tyrannical one-point linear perspective!

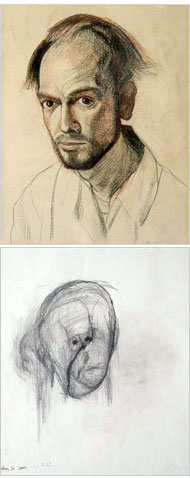

Really awesome article this morning in the NY Times about artist William Utermohlen, who after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease, began drawing/painting self-portraits. The self-portraits, viewed in chronological order, reveal the gradual deterioration of his mind and spirit.

Because Alzheimer affects the “right parietal lobe,” it gets harder and harder to visualize an image and be able to draw it. Art by Alzheimer’s patients becomes “more abstract, the images are blurrier and vague, more surrealistic” and “sometimes there’s use of beautiful, subtle color.”

Looking at these two pieces shoots cold lightning down my spine. It’s so hard to admit to yourself that something you think you do with your heart and soul is really just a bunch of wires connecting your hand to your brain. Maybe it’s for that reason that I find Alzheimer’s to be the most terrifying disease out there.

We’re machines, and machines break down.

I’m also wondering if this Chris Ware quote has any significance:

I see the black outlines of cartoons as visual approximations of the way we remember general ideas, and I try to use naturalistic color underneath them to simultaneously suggest a perceptual experience, which I think is more or less the way we actually experience the world as adults; we don’t really “see” anymore after a certain age, we spend our time naming and categorizing and identifying and figuring how everything all fits together.

And I hate to quote Franzen, but he what about this:

Scott McCloud, in his cartoon treatise “Understanding Comics,” argues that the image you have of yourself when you’re conversing is very different from your image of the person you’re conversing with. Your interlocutor may produce universal smiles and universal frowns, and they may help you to identify with him emotionally, but he also has a particular nose and particular skin and particular hair that continually remind you that he’s an Other. The image you have of your own face, by contrast, is highly cartoonish. When you feel yourself smile, you imagine a cartoon of smiling, not the complete skin-and-nose-and-hair package.

Even towards the end of his abilities, Utermohlen could still make a circle, two dots, and a horizontal line.

Even if it was the face of a ghost, it was still a face.

The book I’m working on includes a kind of memory plot: the main character retrieves his lost memories by retracing his steps, moving through the geographical spaces of his past.

This idea is nothing new: pretty much every character who goes through some kind of trauma in literature deals with it by retracing his steps. Telling his story. Beginning with Odysseus, and more recently, Eternal Sunshine, Memento, Time’s Arrow, Slaughterhouse-Five, etc. These great stories do exactly what they’re supposed to: not only do they give us a map and take us on a journey, they give us a new way of mapping our own lives. (I remember stumbling out of the theater after watching Memento, barely able to read the street signs.)

So this morning I’m reading the good ol’ Science Times, and I get another shocker: according to a recent article published in the Journal of Cognitive Science, “the speakers of Aymara, an Indian language of the high Andes, think of time differently than just about everyone else in the world. They see the future as behind them and the past ahead of them.”

It seems that humans began conflating time and space long before Einstein ever picked up a piece of chalk. Instead of equations, however, we use what are called conceptual metaphors, in which space sits in for time.

Most of us describe the future as ahead or in front of us, and the past as behind us. Until the view of the Aymara speakers was deconstructed, no significant exceptions to this way of thinking about time had been demonstrated….

…the Aymara call the future qhipa pacha/timpu, meaning back or behind time, and the past nayra pacha/timpu, meaning front time. And they gesture ahead of them when remembering things past, and backward when talking about the future.

…the Aymara speakers see the difference between what is known and not known as paramount, and what is known is what you see in front of you, with your own eyes.

The past is known, so it lies ahead of you. (Nayra, or “past,” literally means eye and sight, as well as front.) The future is unknown, so it lies behind you, where you can’t see.

Well, this really blew my mind, and has obvious implications for the story I’m trying to tell. If the future is behind us, and the past up ahead, do we back away from the past, trying to edge closer to the future, but still blind to it? Or do we try to put the past behind us, and are therefore doomed to bump into it in our quest to make it into the future?

I think it also has something to do with comics, another “conceptual metaphor…in which space sits in for time”:

page from REINVENTING COMICS, quoted by Dylan Horrocks

Of course, Dylan Horrocks and James Kochalka toss this theory on its head: comics don’t just spacially represent time, “comics create a world, a place. Instead of SPACE = TIME, this is SPACE = SPACE.”

I’m not sure where my thoughts are headed at this point, but how curious to me that we must map time in order to conceptualize it. That we all seem to be cartographers, trying to map our worlds…

This site participates in the Amazon Affiliates program, the proceeds of which keep it free for anyone to read.