A story is told in images.

You can do it with words, you can do it with pictures, or you can do it with both.

For those interested in doing it just with pictures, there are two books in print right now on woodcut novels and wordless books that are absolute must-reads. First, for an overall sampler and history of the form, get David Beronä‘s Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Beronä is the Library Director of the Lamson Library at Plymouth State University, and he’s been researching woodcut novels and wordless books for twenty years.

Beronä begins with the granddaddy of it all and my personal favorite, woodcut artist Frans Masereel, and points out three major elements that were in the air when Masereel started to create his works:

1) the revival of the woodcut, mostly thanks to the German Expressionists

2) silent cinema, and a “public already familiar with black-and-white pictures that told a story”

3) newspaper cartoons

Beronä goes on to trace the development of the form, including some of my other favorites: the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward (whose name spelled backwards is “draw”) and Otto Nuckel, Milt Gross’s cartoon novel He Done Her Wrong, and Istvan Szegedi Szuts’ ink + brush piece My War.

In the book’s introduction, the the fantastic cartoonist and scratchboard genius Peter Kuper mentions the biblical story of the Tower of Babel and locates wordless woodcut stories as part of humanity’s ongoing quest to use images and symbols to “sidestep our language barriers and create…stories that can be universally understood.”

“Looking for similarities among these artists you find that many share a contrasting use of black and white, dark and light, with a dash of yin and yang. Most also share a connection through choice of materials. From wood engraving to leadcut to linoleum printing, these artists have chosen a medium with a process beyond the immediacy achieved of putting pen to paper. There is a unique quality to these print images that is arresting and iconic. It’s as thought the art were announcing a rally and needed to be read as easily on a lamp post as seen in a book.”

It’s no coincidence that Otto Neurath turned to woodcut artist Gerd Arntz to create the symbols for his celebrated Isotype system of pictorial communication. There’s something in the stark black and white of woodcut and ink and brush that leads to that iconic quality…

…which brings us to the second book and perfect companion to Wordless Books, Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels, which collects in their entirety Frans Masereel’s The Passion of a Man, Lynd Ward’s Wild Pilgrimage, Giacomo Patri’s White Collar, and Laurence Hyde’s Southern Cross. The book was edited by woodcut artist and printmaker George A. Walker. From Walker’s introduction:

As a woodcut artist, I’ve always been attracted to black-and-white art. I think it has something to do with the rich contrasts. I love a deep rich black that you can stare into, forever. The effect is like our colorful world torn down to its base so that we can read the unerlying message. The truth is always easier to take in black and white. Typography is always more legible in black and white, so why would we be surprised to find the readability of artworks enhanced by those contrasts? Remove the grays and hues, reduce the image to lines and solid blacks, and open up the whites. You have a thing of beauty and simplicity.

Another way to understand our attraction to black and white is through the science of how we see. The human eye consists of rods and cones that process the reflected light of our world. These signals are then translated into color and form for processing by our brain. The rods, which are sensitive only to black and white, are the first components activated in a baby’s eyes. That’s why infants readily respond to high-contrast black-and-white images. We are hardwired to appreciate black-and-white artwork.

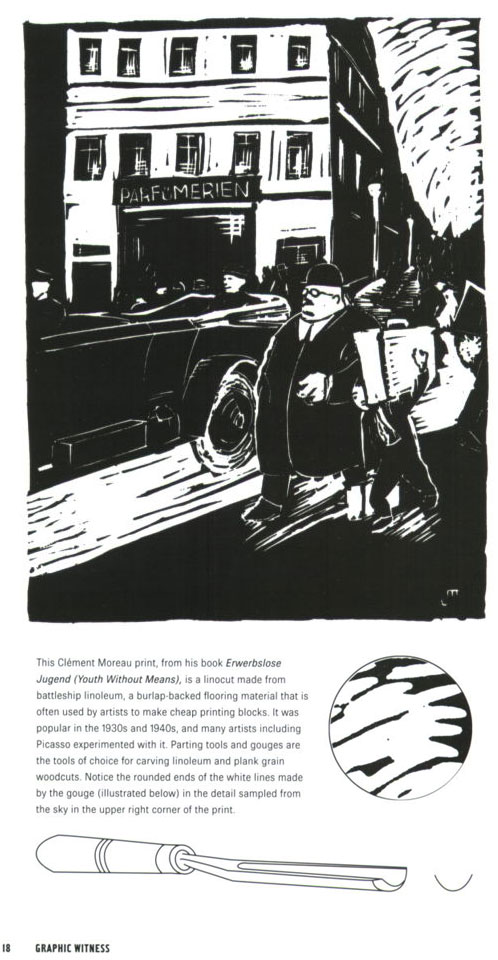

In addition to the great service of publishing these complete works together, the introduction to the book gives a history and overview of relief printmaking techniques (see this MOMA infographic, “What Is A Print?“), focusing on the tools used to create the images:

As anyone who’s familiar with my comics and illustration work should know, I owe a great debt to this form and these artists, and I can’t wait to finish this book of words, so I can get back to making stories out of pictures again! (For those who haven’t seen my previous feeble attempts, see: “Birdseed,” “After the War,” and my abandoned graphic novel, “A Terrible Calamity At Sea!“).

And for those interested in digging further into this subject, check out my Amazon Listmania! List for Wordless Graphic Novels + Comics.