In 1965, the writer William Burroughs was interviewed by the Paris Review. He was 50, living in a hotel in his hometown of St. Louis. A short time later, across the pond, an artist named Tom Phillips read the interview, and decided to play with Burroughs’ cut-up method by doing “column-edge” poems with the New Statesman. He decided to take the method a bit further. He walked to a bookshop, and grabbed the first book he could find for 3 pence. He started blacking out the words, first with just a pen. It was beginning of a 40-year project now known as A Humument.

It’s easy to see how Phillips was inspired: this interview presents a brilliant mind at work, thinking about images and words and writing and how they go together. Burroughs claimed he was most interested in “dreams” and the “juxtaposition of word and image”: “precisely how word and image get around on very, very complex association lines.” He was an avid user of scrapbooks, kept files of newspaper clippings and photographs for character studies, and always wrote down his dreams. He also had a really interesting method of journaling: in three parallel columns, he would record the day’s events, his memories and what he was thinking at the time, and quotes from what he was reading. He called all this “taking coordinates”—a kind of “time travel” to see if he could “project” himself into one single point in time.

Combine this interview with the terrific Beat exhibit I saw earlier this year, and consider me impressed. (I confess that I’ve never made it through any of his books—first up on my list is his collaboration with Brion Gysin [the man who REALLY deserves most of the credit for the cut-up technique…more on that later], The Third Mind.)

Some of my favorite bits:

Seeing

Most people don’t see what’s going on around them. That’s my principal message to writers: For Godsake, keep your *eyes* open. Notice what’s going on around you. I mean, I walk down the street with friends. I ask, “Did you see him, that person who just walked by?” No, they didn’t notice him.

Writers and technology

I think that words are an around-the-world, oxcart way of doing things, awkward instruments, and they will be laid aside eventually, probably sooner than we think. This is something that will happen in the space age. Most serious writers refuse to make themselves available to the things that technology is doing. I’ve never been able to understand this sort of fear. Many of them are afraid of tape recorders and the idea of using any mechanical means for literary purposes seems to them some sort of a sacrilege.

The origins of the cut-up technique

A friend, Brion Gysin, an American poet and painter, who has lived in Europe for thirty years, was, as far as I know, the first to create cut-ups. His cut-up poem, Minutes to Go, was broadcast by the BBC and later published in a pamphlet. I was in Paris in the summer of 1960; this was after the publication there of Naked Lunch. I became interested in the possibilities of this technique, and I began experimenting myself. Of course, when you think of it, The Waste Land was the first great cut-up collage, and Tristan Tzara had done a bit along the same lines. Dos Passos used the same idea in ‘The Camera Eye’ sequences in USA. I felt I had been working toward the same goal; thus it was a major revelation to me when I actually saw it being done.

Objections to the cut-up technique

There’s been a lot of [objections to the cut-ups], a sort of a superstitious reverence for the word. My God, they say, you can’t cut up these words. Why can’t I? I find it much easier to get interest in the cut-ups from people who are not writers—doctors, lawyers, or engineers, any open-minded, fairly intelligent person—than from those who are….People say to me, “Oh, this is all very good, but you got it by cutting up.” I say that has nothing to do with it, how I got it. What is any writing but a cut-up? Somebody has to…*do* the cutting up. Remember that I first made selections. Out of hundreds of possible sentences that I might have used, I chose one.

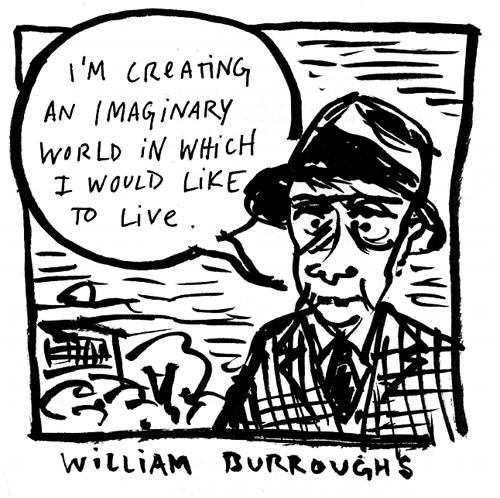

World-building

You know, they ask me if I were on a desert island would I go on writing. My answer is most emphatically yes. I would go on writing for company. Because I’m creating an imaginary—it’s always imaginary—world in which I would like to live.

Any fans of Gysin or Burroughs out there? What texts would you recommend?