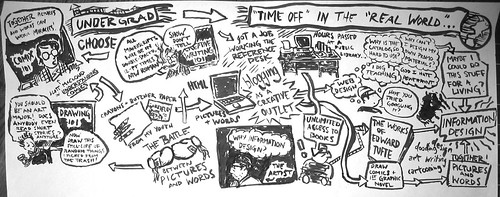

Here’s another map I did with the ol’ sumi-e brush for an essay I’m working on. The piece of paper was really huge, so I had to take a photo with the digital camera. I had all this random junk floating around my head for the essay, but I couldn’t figure out how to put it in linear, narrative form. I started out thinking this would be another radial map (I started with the black box in the bottom-middle), but it ended up with a horizontal flow (what you see is only the top half of the sheet). This was a happy accident, and in the process of drawing the map, I realized the narrative that was hiding amongst all the random junk.

The quote by McCloud in the top, lefthand corner is from chapter 6 of UNDERSTANDING COMICS, “Show and Tell.” Notice the creative writing professor repeating the mantra of workshop: “Show, don’t tell!”

(I should note that even though I often take shots at creative writing workshops, my own workshop professor was wonderful: I took all my workshops at Miami from him, and he is still a good friend of mine. He’ll even be at the wedding!)