IN THE LOCKER ROOM

“YOU LOOK JUST LIKE THAT GUY WHO GOT SHOT ON CSI LAST NIGHT”

“You look just like…”

I’ve heard Robert Downey Jr. and Donnie Darko, but now it’s “that guy who got shot last night on CSI.”

What do you say to this stuff?

I get this brand of couch potato free-associating day in and day out at the reference desk. And it’s always from someone in sweatpants. Never someone you’d actually want a compliment from.

“Thank you, I’m glad I remind you of a celebrity, even a minor one. My sense of self-worth has sky-rocketed.”

Okay, enough griping.

They have nothing to do with this post, but I like pretty much everything that Tom Gauld, Anders Nilsen, John Porcellino, and Kevin Huizenga put out.

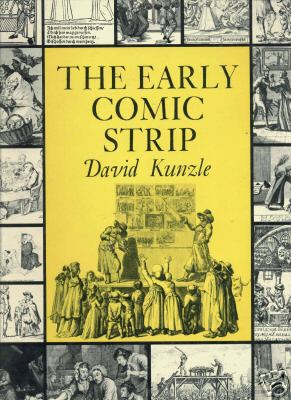

R. CRUMB ON COLLECTING AND DAVID KUNZLE’S THE EARLY COMIC STRIP

R. Crumb talks about David Kunzle’s The Early Comic Strip in Todd Hignite’s excellent In The Studio: Visits With Contemporary Cartoonists:

My awareness of this whole history was something that happened gradually, since that stuff is not available. Where are you going to see it? You’d have to go to some library that specializes in that and ask to look at it. It’s not reprinted anywhere, so it’s not known. So when I got that big book by Kunzle, it was a total surprise, how much material there was, and I’m sure that’s still just a drop in the bucket, you know, what survived, what he could get his hands on, and what he could actually show — I’m sure he could have done twice as much. So much of them are so crude, those little, postage stamp-sized panels of, like, husband-and-wife squabbles done in Russia or Germany or Czechoslovakia. Incredible stuff, but totally obscure. If you try to inform people in the art world of this history, they know nothing about it. A complete underground, unknown, history of popular art that the general art world knows nothing about. When Alfred Fischer, the curator of my show in Germany [at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne] came, I showed him this book and some other things and he was just speechless; it was all completely new to him. The crude, lowest level of popular arts.

What I love about Hignite’s book is that it focuses most of its attention on the cartoonists’ influences, personal libraries, and thoughts about the history of the form. As Hignite comments, “To varying degrees, these artists are collectors themselves, so the process of creating is interwined with other art: the working studio is also library archive, and museum.” Later in his interview, Crumb goes on to lament the difference between this kind of collecting versus “academic” interests:

It’s just that academia’s interest in this stuff is so lame….There’s a big difference between a collector-archivist and people in academia….In academia they get locked into this thing of having to narrow it down and narrow it down to this very particular specialty that they focus on, and they’re very proprietary about it, so that it scares them to actually scan the culture at large as we do and just pick out, “Oh, this is interesting,” o, “That’s interesting from this whole different area,” and then look into it; that’s a waste of their time. There are probably exceptions, but it gets narrower and narrower as there get to be more academic specialists and specialties. You have to be so specific about “you” things, and if someone else who’s not the expert volunteers some information, then it’s almost a threat.

More and more, my vision of comics as a type of collage — a spattering of pictures, words, influences, events, personal histories, books, whatever…go read the Lethem article, where he says, “In fact, collage…might be called the art form of the twentieth century, never mind the twenty-first.” — synched together in a unity of style, grows and strengthens in my head. Which is why reading — ammassing influence — is such an important part of the gig…

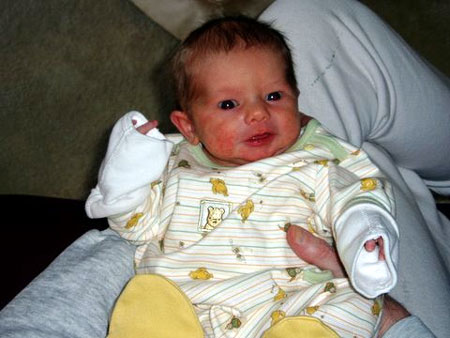

I’M AN UNCLE!

Anthony Kleon, Jr. was born two days ago.

Look at that hair!

- ← Newer posts

- 1

- …

- 557

- 558

- 559

- 560

- 561

- …

- 635

- Older posts→