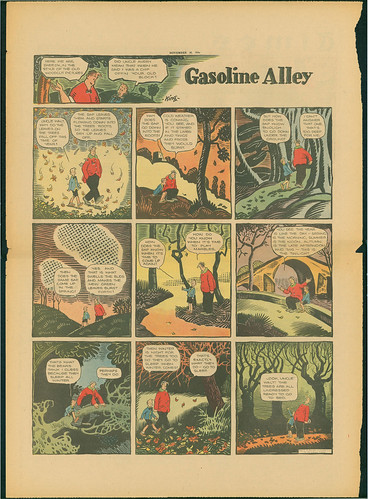

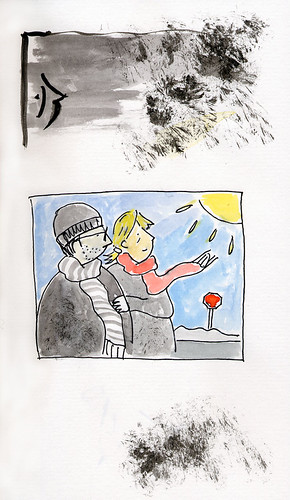

Supposedly, Chris Ware loved this particular Gasoline Alley strip by Frank King so much that he tore the page out of the Smithsonian Collection Of Newspaper Comics book and had it mounted on the wall of his studio. Given my fondness of the “style of the old woodcut pictures,” I had to rip it off, myself.

I got this great tear sheet scan from Roger Clark’s fantastic archive of annual Gasoline Alley “autumn walk” Sunday pages.