WHY NOT MAKE IT A MONOLOGUE?

For someone who loves stories so much, I’m a terrible oral storyteller. I get the pacing wrong, bungle the chain of events, forget who said what when…. Oral storytelling is a performance, and I’ve always had a hard time with performance. It’s one of the reasons I knew I’d never be a real musician: I always preferred recording on a four-track to singing at the open mic night.

I spent a good hour yesterday in the barber’s chair, telling “The Ballad of Austin and Meghan” to the girl cutting my hair. Since getting engaged, I’ve told the story at least a dozen times, and each time I feel like I never do it justice. Maybe that’s why for our wedding favors, Meg and I want to make a mini-comic about our lives together up until this point. To tell the story and to get it right!

For months I’ve been thinking about what form it should take. At first I thought it should look like a Lynda Barry or a James Kochalka, with the narration covering large gaps of time, and the pictures singling out individual moments and bits of dialogue. (This might be a good place to point out that the usual adage in creative writing class, “show don’t tell,” is useless in the medium of comics — you can show and tell all you want.) But somehow, that idea just didn’t seem right, so I put off starting on it.

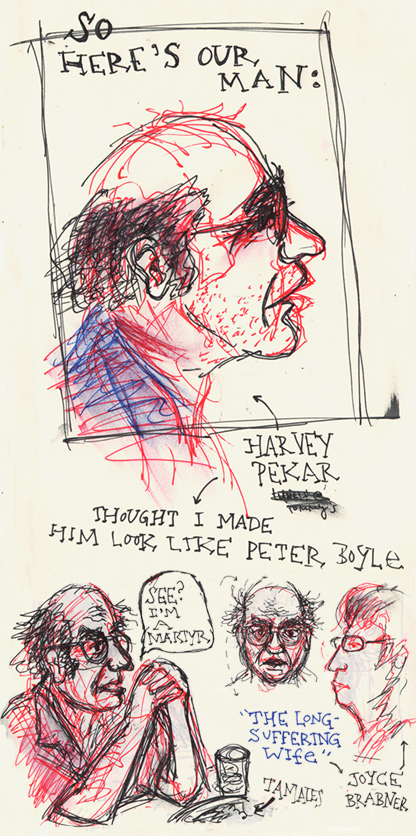

Then I started going through my old American Splendor anthology, and came across one of my favorite Crumb/Pekar collaborations:

(If you’ve seen the movie, this story was adapted into a great Paul Giamatti monologue.)

With background, facial expressions, hand gestures, pauses, and other visual cues, comics turns out to be a great way to approximate the experience of oral storytelling. Better yet, you’re not a passive listener — unlike the real-time experience of film or real life, you get to set the rate at which you receive the story. The only thing you don’t get is the sound of the storyteller’s voice.

So, for our mini-comic, it’ll essentially be Meg and I talking to our guests, telling them our story. Only afterwards, they can stick us in their pocket and take us home.

ALISON BECHDEL IN CLEVELAND

After scarfing down some tacos with about 50 soccer brats at the Chipotle across the street, last night we went to see Alison Bechdel read at the Joseph-Beth in Legacy Village. (Here’s Alison’s own blog of the event.) They had the reading hidden upstairs in this special conference room that had a fantastic projector. Then Harvey Pekar got up and gave an introduction that emphasized her skills as a writer:

Genuinely thrilled, Alison said, “That’s like the Grateful Dead introducing Phish.”

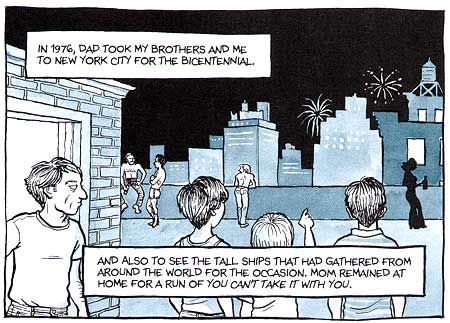

She started out by reading from the first chapter of Fun Home. Using Powerpoint, she projected the individual panels onto the projection screen while she read the narration from a script. (She let the speech bubbles inside the panels speak for themselves.) It was really soothing, and blowing the panels up several times bigger than their actual size you could see every hatch, every stroke, every variation in the inkwash. Meg said it was like seeing slides in architecture studio — you could see the way the imagery was working in a way different from reading the book.

“The thing about doing a graphic novel is that it’s a really physical process,” Alison said. “You have to know every square inch of the book. So there’s no way for me to talk about the book without showing it to you.”

It was truly using Powerpoint for good and not for evil, and I’m convinced now that Powerpoint is the key to presenting comix readings.

After she finished the chapter, she went into a slideshow detailing how she wrote the book.

What blew me away is how much writing leads her process. She used this panel from page 189 to illustrate:

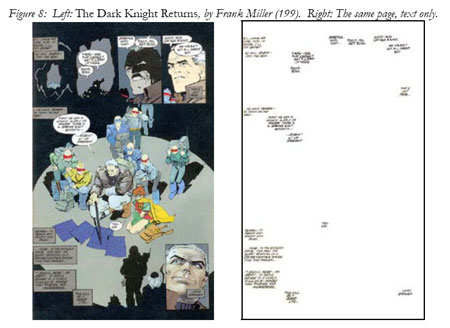

She starts out by using Adobe Illustrator to type out her narration and dialogue into boxes. (She also includes a textual description of how the art will look.) Then she arranges the text around the page how she wants. At this stage, it looks very much like visual poetry. In her senior thesis, an undergrad colleague of mine, Elisabeth Price, reverse-engineered a Frank Miller page this way:

After getting the text just right, she rough pencils the panel on the typing paper.

The next step involves lots of photographic research — for this panel, she researched pictures of gay men from the period, fireworks, rooftops, water towers, and random people sitting on rooftops.

“I couldn’t have done this book without Google Image Search.”

She also takes digital pictures of herself in every pose that takes place in the panel.

“After this step,” she said, “the work is ninety-percent done.”

And yeah, the next steps are pretty standard comics stuff — tight pencil, then inking, erasing the pencil. Then the whole thing is scanned into Photoshop and cleaned up.

She did a gray inkwash for the shading that was later turned green by her publisher.

“It was weird because I never knew how it was all going to come together.”

Watching her describe her process, I thought once again about how I believe that comics is really collage — cobbling together layers of text and images. It’s the style that unifies the work — the style that convinces you that all this stuff is supposed to be in the same place.

After her process presentation, she read from chapter four, and then it was time for questions and answers.

She talked about her relationship with her mom, about the unexpected success of the book, and the bizarre mix of excitement over its success, and the burden of having her family story everywhere. Harvey chimed in by telling an anecdote about Robert Crumb and his reaction to Terry Zwigoff’s documentary about him.

“Crumb didn’t want to be bothered,” Harvey said. “He figured Terry would do the film, and everyone would forget about it.”

Then Harvey’s wife, Joyce Brabner, said: “Crumb’s first wife, Dana, has been trying to get a book published for years. It’s called, It Was My Life Too, Goddamnit!”

Afterwards, Alison signed books. Here’s a funny story about how much of a perfectionist she is:

She was going to draw a portrait of one of the women in line, but she said she didn’t have a pencil. “Does anybody have a pencil?” So I gave her one of those golf pencils you get at Ikea, and she did the sketch, then inked it.

I tried to draw her several times during the night, but just couldn’t get it right. Part of the problem was that I was caught off guard by her looks: from photos, she looks very, well, masculine and angular (butch hair, dark suit, glasses), but when you really start trying to draw her, looking close at her face, you realize that her lines are much softer in real life…

Meg and I, we’re always arguing about whether it’s more invasive to draw someone or take their picture. You certainly see a person much clearer by drawing them.

A lesson that maybe Alison has learned herself.

THE QUITTER

I was driving over to our writer’s group meeting last night, and caught the tail end of Harvey Pekar on Fresh Air with Terry Gross. Great stuff about work and writing:

PEKAR: I knew I couldn’t make money at the stuff I liked to do. So I took a job that was not challenging, and you know, when it was slow at work, I used to sneak into the corner and read or write. It worked out. It was easy, I didn’t have to go home and worry about the work, I just went and did the work, and went home and thought about writing about something.

GROSS: Now that you don’t have your day job…you can write as much as you’d like. I think most writers find it really hard to write for a good deal of the day. You might have dreamed your whole life of having that flexibility, but now that you have it, what’s it like to have it?

PEKAR: That’s a very good question, Terry. It would be pretty hard for me to write, you know 40 hours a week, 8 hours a day, that kind of week like I did when I was at the V.A.

GROSS: Did you have to learn how to deal with an unstructured day–a day that wasn’t structured by a 9-5 job?

PEKAR: Yeah. I did. At first it freaked me out, uh, In fact, I got so depressed and screwed up I was hospitalized for major depression…