Note: spurred on by Mark’s excellent comment on my “new house” post, I’m posting this excerpt from my undergrad thesis I wrote in the spring of 2005 (pre-blog). The thesis was called “Pictures Before Words,” and it was about using visual thinking techniques like clustering and storyboarding to create prose fiction. It’s surprising to read back through it now, and realize how much it laid out the ideas I would explore in the next 3 years or so: sense of place and writing as world-building, the connection between pictures and words…thanks to Sean Duncan for introducing me to a lot of the material!

* * *

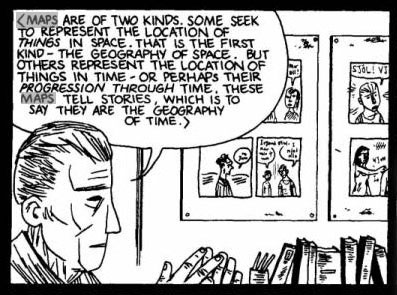

IN CHAPTER FOUR of Dylan Horrocks’ graphic novel, Hicksville, a character named Dylan Horrocks and a character named Grace travel to a land named Cornucopia to meet its greatest cartoonist, Emil Kopen. Upon their meeting, Kopen refers to himself not as a comics writer, but as a “cartographer” or a “maker of maps.” This puzzles Horrocks, and prompts Grace to ask Kopen to explain. Kopen says that comics are the same as maps because they are “using all of language—not only words or pictures.” Horrocks asks Kopen about the purpose of maps.

“Maps are of two kinds,” Kopen explains. “Some seek to represent the location of things in space. That is the first kind—the geography of space. But others represent the location of things in time—or perhaps their progression through time. These maps tell stories, which is to say they are the geography of time.”

This monologue is quite similar to Scott McCloud’s argument about comics in Reinventing Comics. He argues that space is the form of comics, and time the content: comics work by mapping time.

In Horrocks’ online article “Comics, Games and World-Building” (highly recommended) he responds to McCloud’s argument by exploring and expanding the theories of James Kochalka. In Kochalka’s comic, The Horrible Truth About Comics (included in The Cute Manifesto), he proposes an alternative definition of comics to McCloud’s: comics as world-building. “Comics are a way of creating a universe.”

Horrocks interprets:

Now, most discussion about comics (or fiction, for that matter) assumes that their main purpose is to tell a story – a narrative that moves through time; hence McCloud’s description of comics as a “temporal map.” But here, Kochalka seems to suggest something quite different: that comics create a world, a place. Instead of SPACE = TIME, this is SPACE = SPACE.

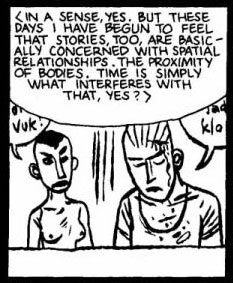

Even those narratives that would seem to be primarily interested with mapping time, with telling stories, or plots, can be seen in spatial terms. Horrocks’ character Emil Kopen explains to the character Dylan Horrocks that along with maps of geography, he feels that “stories, too, are basically concerned with spatial relationships. The proximity of bodies. Time is simply what interferes with that, yes?”

In Writing Fiction, Janet Burroway writes that while plot has often been seen as a type of “power war” or “back and forth” that seems to be going on between characters, “narrative is also driven by a pattern of connection and disconnection between characters that is the main source of its emotional effect.” Connection and disconnection are spatial terms; they imply different degrees of proximity.

Horrocks observes that the notion of “world-building” has mostly been popular within the genre of fantasy (i.e. J.K. Rowling’s Hogwarts, or Tolkien’s Middle Earth). But Horrocks suggests that “all writers are engaged in ‘sub-creation,’ to the extent that all fiction takes place in a ‘Secondary World,’ no matter how closely it may resemble the ‘real world’ in which we live.” No matter what genre you write in, you can use the same world-building techniques used by fantasy artists and writers.

When we read comics and fiction or watch movies, we are asking the artist to take us into a universe of his making. In the words of Kochalka, “When we encounter a great work of art the physical world fades away as we step into this new reality. We are alive in a living world.” This sounds remarkably similar to John Gardner’s idea of fiction as “a kind of dream” that the reader falls into: “We read a few words at the beginning of the book or the particular story, and suddenly we find ourselves seeing not words on a page but a train moving through Russia, an old Italian crying, or a farmhouse battered by rain. We read on—dream on—not passively but actively.”

If writers and cartoonists accept the idea that what they must first do to create a convincing narrative is world-build, the next step is to wonder how they might go about such a thing.

Alan Moore, in the chapter entitled “Worldbuilding; Place and Personality” in Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics, suggests that world-building simply means coming up with the working details of your world and environment before you actually go about writing your story. He suggests coming up with

a mass of information about the world and the people in it, much of which will never be revealed within the strip for the simple reason that it isn’t stuff that’s essential for the readers to know and there probably won’t be space to fit it all in. What is important is that the writer should have a clear picture of the imagined world in all its detail inside his or her head at all times.

Moore suggests that gifted writers will avoid dropping huge amounts of detail on the reader at one time, but instead use these details sparsely in each frame, to suggest that there is a world going on outside of the frames of the comic. This idea parallels Scott McCloud’s theory of closure—“the comics creator asks us to join in a silent dance of the seen and the unseen. The visible and the invisible.” The comics reader is required to fill in the details of the world going on outside the comic panel, and this will succeed only if the world is concretely realized by the creator.

My argument is that the artist can see written fiction, comics, and film as multiple disciplines on the spectrum of storytelling. Although they all have different ideas about what a story is and how you build and present a story, if we accept that what each discipline does is world-build, then we can use the term “world-building” to move fluidly between disciplines. When we have the world-building tools and processes mastered from multiple disciplines of storytelling—whether it be drawing in the case of comics, or writing in the case of fiction—we can use these tools and processes across disciplines to generate the worlds that we imagine.

Recommended reading:

- Dylan Horrocks, Hicksville

- Derik Badman’s review of Hicksville (there’s a paragraph about the “maps” section)

- Dylan Horrocks, “Comics, Games and World-Building”

- James Kochalka, The Cute Manifesto

- Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics