The drawing skills don’t matter. It’s can you get down on paper what’s in your head? And if you can in such a way that when I read it you’re opening up a new eye to the world for me or a new ear to the how people talk, or what have you…then it’s cookin’. It’s comics. And that’s all that matters.”

– Steve Bissette, from the really great little trailer for Tara Wray’s documentary, “Cartoon College”

THE GHOST OUTLINE OF A FACE

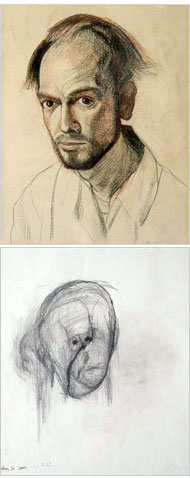

Really awesome article this morning in the NY Times about artist William Utermohlen, who after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease, began drawing/painting self-portraits. The self-portraits, viewed in chronological order, reveal the gradual deterioration of his mind and spirit.

Because Alzheimer affects the “right parietal lobe,” it gets harder and harder to visualize an image and be able to draw it. Art by Alzheimer’s patients becomes “more abstract, the images are blurrier and vague, more surrealistic” and “sometimes there’s use of beautiful, subtle color.”

Looking at these two pieces shoots cold lightning down my spine. It’s so hard to admit to yourself that something you think you do with your heart and soul is really just a bunch of wires connecting your hand to your brain. Maybe it’s for that reason that I find Alzheimer’s to be the most terrifying disease out there.

We’re machines, and machines break down.

I’m also wondering if this Chris Ware quote has any significance:

I see the black outlines of cartoons as visual approximations of the way we remember general ideas, and I try to use naturalistic color underneath them to simultaneously suggest a perceptual experience, which I think is more or less the way we actually experience the world as adults; we don’t really “see” anymore after a certain age, we spend our time naming and categorizing and identifying and figuring how everything all fits together.

And I hate to quote Franzen, but he what about this:

Scott McCloud, in his cartoon treatise “Understanding Comics,” argues that the image you have of yourself when you’re conversing is very different from your image of the person you’re conversing with. Your interlocutor may produce universal smiles and universal frowns, and they may help you to identify with him emotionally, but he also has a particular nose and particular skin and particular hair that continually remind you that he’s an Other. The image you have of your own face, by contrast, is highly cartoonish. When you feel yourself smile, you imagine a cartoon of smiling, not the complete skin-and-nose-and-hair package.

Even towards the end of his abilities, Utermohlen could still make a circle, two dots, and a horizontal line.

Even if it was the face of a ghost, it was still a face.

A FEW THOUGHTS ON PEANUTS

I’ve been on another obsessive Peanuts-reading tear. If you’re interested in listening in to the conversations of one of the greatest geniuses of the 20th century, I highly recommend Charles M. Schulz: Conversations. Particularly wonderful is the 100+ page interview with Gary Groth from 1997 that ran in the Comics Journal.

Two things that strike me right this second about the strip.

First, I’ve been thinking about the difference between reading comics in serialized form — in newspapers or seperately published editions over time — and reading them in book form. Schultz himself said that comics strips weren’t art because they were “too transient” to appeal to several generations. But the act of collecting Peanuts into books, or “treasuries,” basically has cemented their status as great art. Because the characters are so strong, and the world is so static over time, Peanuts is an epic of gag strips — in book form, it really does amount to what George Saunders called a “50-year novel.”

Second, I’ve been thinking about the way in which Schultz’s drawing led his ideas. His formal innovations with his drawing — dressing Snoopy up as a fighter pilot, for instance — led to his character and story development.

Take the character of Schroeder. Schultz said:

“I was looking through this book on music, and it showed a portion of Beethoven’s Ninth in it, so I drew a cartoon of Charlie Brown singing this. I thought it looked kind of neat, showing these complicated notes coming out of the mouth of this comic-strip character, and I thought about it some more, and then I thought, ‘Why not have one of the little kids play a toy piano?'” (*)

Schultz made sure to recreate exactly those Beethoven musical scores by hand, and it was the act of drawing — the simple aesthetic pleasure of musical notes in a comic strip — that led to Schroeder.

What this means to me is that drawing comics is its own particular brand of alchemy. You can’t just sit down and say, “I’m going to draw a character with a funny nose who has no father and always trips over his shoelaces.” The description means nothing. You have to draw that character into existance.

It’s the act, not the idea.

KEY TO A MAN’S HEART, PT. 3

“A man might go out and paint a beautiful landscape or a beautiful picture of the human figure, but he is copying nature. Men who paint or draw from life — roses, skies, objects of this and that, still life, etc. — are merely copying what they see. They are called artists. The cartoonist must create, he must see in his mind a situation, maybe full of life and comedy, maybe still of dramatic or tragic. He must draw it with all the feeling in him — without models or other aids that artists call to hand.”

– Winsor McCay, “On Being A Cartoonist,” reprinted in Daydreams and Nightmares

I wonder what McCay would’ve said about Google image search?

* * *

I’m getting back into work on Calamity, after a brief, stress-relieving hiatus. Working on “Key” has really made me realize how much I miss working with pen and paper — how essential rough sketches and ink on the fingers is to the whole project of making comics. Working on short, quickly-finished projects while working on a longer, drawn out project seems to be the way to go for me…I still say the best way to work with comics is to write short strips and storylines around the same characters/setting and then later weave them into a lengthier narrative for publication.

* * *

Part of my job at the library is teaching computer classes to (mostly) elderly patrons. Eventually, I want to write a long, lengthy post about this experience, but for now, I’m meditating on my own thoughts and feelings about old folks.

The good part of me wants to reach out to them, listen to their wisdom, and help them navigate the technology-obsessed terrain that is modern life. This part of me wonders why we don’t refer to them as “The Elders,” and seat them at the prime spot in front of the campfire to give advice to the tribe, instead of shuffling them away to nursing homes.

But then there is an ugly part of my being that wants to reject old folks — this is the part that doesn’t buy into the “Greatest Generation” Tom Brokaw crap, that blames the supposedly righteous and untouchable WWII generation for our current problems, that doesn’t respect the “I’ve been here longer than you so I have a right to be cranky” rule, and that wonders why those who can’t take care of themselves don’t say goodbye to their friends and family and walk out into the frozen wilderness.

Anyways, I guess what I’m thinking about is usefulness. People have to have a purpose. A place. An individuality, but also a role within a larger community. How do we accomplish this?

The singularity is near. What are we going to do with all these old people?

SOME THOUGHTS ON FUN HOME

Last night I finished Alison Bechdel’s excellent comics memoir, FUN HOME. I don’t have a whole lot to add to the raves (it’s been on on NPR, it’s gotten fabulous reviews, it’s selling like hotcakes all over), but it probably ranks up there with some of the best graphic novels I’ve ever read.

While it’s a genuinely enjoyable read, with a subject matter as engrossing and complex as any prose memoir, the carnivorous, thieving cartoonist in me solidified some of my feelings about the form, and found some good things to steal…

Disclaimer: Gerry over at Backwards City recently linked to this Wired article about academics at Comic-Con, so more than usual, I’m fully aware that writing about comics is pretty lame. “You have this dog and you love it, and you want to find out why you love it. You dissect it, and you’re left with this dead bloody dog on the table. That’s one of the things that academics do.” But I’m going to do it anyways, and haphazardly at that.

JUXTAPOSITION OF VOICEOVER NARRATION AND IMAGE/DIALOGUE

For me, the greatest technical accomplishment in FUN HOME is the juxtaposition of Bechdel’s written, first-person narrative with her panels and speech bubble dialogue. This might be a “duh” observation, as word/picture juxtapostion is something you might take for granted as a pre-requisite for comics, but that’s simply not the case. Take something like Brian K. Vaughn’s equally excellent Y: THE LAST MAN, for instance: it plays out like a really intricate movie: there is no narrator, only a camera’s eye. The same for most gag strips, like PEANUTS and KRAZY KAT: there is no narrator, only the characters and speech bubbles.

What voiceover narration (for lack of a better term) allows you to do in comics is make bigger jumps in between moments in time and images, thereby freeing you from the kind of static, talking head syndrome of plays or scenes in film. It also, through juxtaposition, allows you to cram a bunch of information into a tiny amount of space. My favorite folks who use the technique (and consequently, my favorite cartoonists) are Lynda Barry and James Kochalka. What it really is, I think, is the perfect integration of writing and art.**

Anyways, in creative writing classes, they’re always harping at you to show, not tell.*** Use concrete language verses abstract language. If you notice, much of the voiceover narration is ridiculously abstract, but combined with the concrete images and dialogue of the panels, you get this sweeping, novelistic effect…a soothing voice that takes your reader by the hand and leads them through the world, reflects on what is happening. Less voyeuristic, I guess, and more like a tour…

RECURSIVE NARRATIVE, ARCHIVAL ELEMENTS, AND THE UNITY OF STYLE

As Hillary Chute in her Village Voice review pointed out, “Fun Home ‘s narrative is recursive, not chronological—it returns again and again to central, traumatic events.” This is something that I think begs to be looked at in terms of world-building. FUN HOME isn’t so much a chronological retelling of events as much as it is a world.

Dylan Horrocks, once again:

…the panel is a unit not of time or space, but of meaning (a kind of sememe). And rather than being arranged in a sequence, Kochalka’s units are arranged in rhythmic patterns. The purpose of these patterns, he claims, isn’t merely to depict the flow of time, but to “create and activate a world inside us.”

Now, most discussion about comics (or fiction, for that matter) assumes that their main purpose is to tell a story – a narrative that moves through time; hence McCloud’s description of comics as a “temporal map.” But here, Kochalka seems to suggest something quite different: that comics create a world, a place. Instead of SPACE = TIME, this is SPACE = SPACE.

Bechdel returns again and again to maps and explaining events in geographical terms, and FUN HOME is like a map of Bechdel’s brain, and her archive: it contains “handwritten letters from [her] father, typewritten letters from both her parents, her father’s police record, dictionary entries, her own childhood and adolescent diaries, and many maps. Bechdel re-drew—re-created—everything in her own hand.”

That Bechdel chose to re-draw all these elements in her own hand is a trick to graphic novel writing: the style unifies the disparate elements, so you can turn to any page, and it looks like it comes from the same world, filtered from the same mind.

Okay, that was kind of a pantload. I promise tomorrow I’ll just post a pretty picture and call it a day.

**Dylan Horrocks recently said on his blog: “[Comics] allow you to be both an artist and a writer all at once. And many (James Kochalka is one example who comes to mind) seem to me to defy any attempt to place them in either of two such arbitrary ‘camps.’

***which makes me wonder, really, if there’s any hope for applying the MFA workshop format to making comics. Check out this great interview with Francine Prose about the sorry state of MFA programs.