SCRAPS

[Hillary Clinton] must be the first presidential candidate in history to devote so much energy to preaching against optimism, against inspiring language and — talk about bizarre — against democracy itself.

— Frank Rich, “The Audacity of Hopelessness“

I saw there was no reason to think that [comics] were intrinsically a limited form… ‘Cause you could choose ANY word that was in the dictionary… You got the same choice of words as SHAKESPEARE… and you got a huge variety of art styles that you could use. Comix are WORDS and PICTURES… WORDS AND PICTURES… you can do ANYTHING with WORDS and PICTURES…— Harvey Pekar

I asked my mother, what should I teach my kids? She said don’t teach them anything, just give them lots of supplies.— Tony Millionaire

Don’t piss on my leg and tell me it’s raining.— Judge Judy

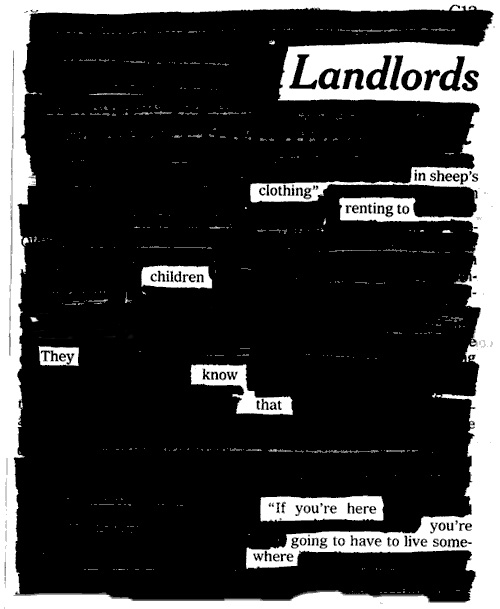

LANDLORDS IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING

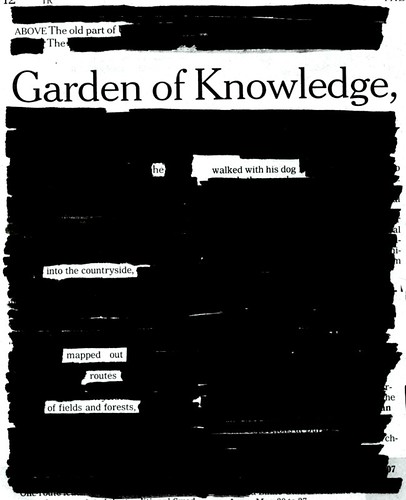

OUTSIDE THE GARDEN OF KNOWLEDGE

TIME BECOMES STRANDED

- ← Newer posts

- 1

- …

- 509

- 510

- 511

- 512

- 513

- …

- 635

- Older posts→