My car is sitting in a tow yard in south Austin. The side of the driver’s window is messed up from the break-in, the ignition has been torn out, and the windshield looks like somebody threw a bottle at it. The thieves ate our Chex-Mix, took our Ipod adapter, but left our cowboy hats, umbrellas, and flip-flops. They took it for a 100-mile joyride (I know, because I had just got gas, and flipped the odometer) and dumped it in a parking lot.

Tommy-the-Tow-Guy and I, we put in the clutch, stuck a screwdriver in the ignition, and she fired up like nothing happened. It’s totally drivable, but we have to get the insurance company out to assess the damage before we can drive off with it and get it repaired.

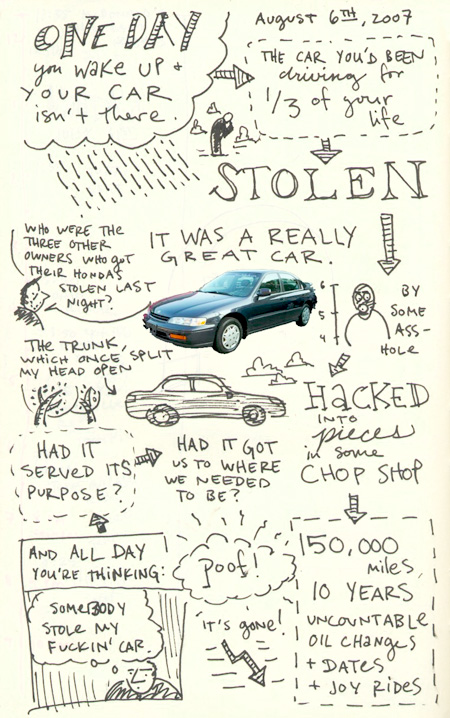

So add this to the news that as of tomorrow, I will probably be employed, Meg and I are very happy. Here’s what I doodled last night, thinking I’d never see her again:

Even taking into account the car theft, we’re having a really fabulous time in Austin. Here’s the sunset over Lake Travis that we got to see last night:

Can’t beat that.